To what Extent do the Public Need Educating about Eating Disorders?

Harrison A and Bertrand S

DOI10.21767/2471-8203.100026

Harrison A* and Bertrand S

Faculty of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, School of Psychotherapy and Psychology, Regent’s University London, Inner Circle, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4NS, UK

- *Corresponding Author:

- Amy Harrison

Faculty of Humanities

Arts and Social Sciences, School of Psychotherapy and Psychology

Regent’s University London

Inner Circle, Regent’s Park, London

NW1 4NS, UK

Tel: +44 203 075 6184

E-mail: harrisona@regents.ac.uk

Received date: July 11, 2016; Accepted date: October 21, 2016; Published date: October 28, 2016

Citation: Harrison A (2016) To what Extent do the Public Need Educating about Eating Disorders? J Obes Eat Disord 2:2. doi: 10.21767/2471-8203.100026

Copyright: © 2016 Harrison A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Previous studies highlight poor education around eating disorders (EDs) amongst the public, alongside negative attitudes towards those affected by EDs, which may reduce opportunities for help-seeking. Little is known about whether improved education regarding EDs gained through experience might impact negative attitudes and to attract government funding for public education campaigns, greater knowledge around levels of education is required.

Methods: Semi-structured interviews were conducted to investigate ED education in 10 adult women with experience of an ED attained through a close loved one’s illness and 10 women without experience. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data.

Results: Four themes endorsed by both groups emerged from the data: 1) general education (of individuals, society, health professionals); 2) education regarding the specific nature of the illness (role of food, addiction, severity, impact); 3) knowledge regarding aetiology (biological and social factors, self-esteem and the media); 4) hope and the future (sympathy, empathy and positive outcomes). Experienced participants reported higher education than inexperienced participants although knowledge gaps were observed across all participants and while strong negative views were not expressed, the experienced group offered greater empathy.

Conclusion: The general public are relatively poorly educated about EDs and public education programmes are warranted, targeting the above themes, which appeared to be salient to lay individuals.

Keywords

Eating disorders, Public health education, Anorexia nervosa, Bulimia nervosa, Mental health literacy, Stigma

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) including anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) are serious mental health difficulties [1] associated with severe physical complications and functional impairment [2]. Although EDs have a complex and multifaceted etiology [3], they appear to have a strong genetic component [4-6], although this is not widely known by the public, who instead tend to endorse the socio-cultural environment, in particular, the media, as the key etiological agent [7]. Indeed, previous research highlights a significant gap in education amongst the general public regarding EDs, with the seriousness of the illness grossly underestimated, such that the public have endorsed a view that EDs are experimental phases [7], and not ‘real’ mental health difficulties [8], at odds with their status as life-threatening mental disorders [2]. Furthermore, misinformed, negative attitudes towards those with EDs are also reported amongst the general public, including the view that those with EDs are wealthy, white, “self-centered” adolescent girls [8] for whom recovery is a case of ‘pulling themselves together’ [9,10]. Some lay people have expressed admiration and a desire to mimic ED behaviours [11], with the belief and such behaviours are performed willingly by individuals with EDs [12].

The stigma expressed towards individuals with all forms of mental health difficulties is well documents [13-15]. However, evidence highlights greater stigma is directed towards EDs compared to other mental health difficulties including depression [11] and the public report being less willing to provide social support to people with EDs than other those with other mental health conditions [16]. Poor education around EDs is not limited to the general public and has also been reported amongst health professionals, who may share similar misinformed negative attitudes [17] and highlight their own education gaps [18].

A lack of education amongst the general public around EDs may have negative consequences including high levels of selfstigma, where the individual holds negative attitudes towards their own illness, a factor which reduces help-seeking for EDs [19]. This is concerning given that EDs are associated with low help-seeking more generally, with only 17% of those at risk seeking help [20-22], and instead, the illness becomes valued by the individual themselves [23]. Poor education and negative attitudes amongst the general public may also increase shame [24] and feelings of low self-esteem [25], further hampering the likelihood of sharing experiences which is concerning because evidence highlights the importance of involving close others in fighting EDs [26]. Taken together, these findings highlight that improved education amongst the general public regarding EDs may reduce perceived barriers to treatment [27].

Having contact with individuals with mental health difficulties improves education and reduces negative attitudes [28,29] and it is possible to improve awareness and understanding amongst the general public via educational initiatives [30-33]. However, these studies primarily focused on schizophrenia and little is known about whether contact with an individual with an ED improves education and reduces the negative attitudes held towards those with EDs [34]. Furthermore, many previous studies investigating public education regarding EDs have utilised quantitative methodologies and greater qualitative feedback may enhance the evidence base around public knowledge of EDs which could further strengthen the case for the funding of public education programmes around EDs.

Therefore, this study has two aims: The first is to enhance the evidence base regarding public education around EDs by conducting a qualitative investigation of the general public’s knowledge and attitudes towards EDs. The second is to explore whether contact with an individual with an ED impacts education around EDs. In keeping with this form of methodology, no specific hypotheses are stated at the outset.

Method

Participants

Due to previously noted gender differences in attitudes towards individuals with EDs [34], female participants were recruited to limit possible confounds in this exploratory study. Two groups of participants were recruited. The ‘experienced’ participants were approached via an advert circulated via an ED charity (Anorexia and Bulimia Care; ABC) and were included if they had supported a loved one (a family member or close friend) with an ED for at least 1 year, and have regular contact with the individual (defined as meeting their loved one on at least 4 occasions per week, alongside other contact such as phone calls and text messaging). The ‘inexperienced’ participants were required to have had no extended contact with an individual with an ED at any point in their lifetime and, ascertained through a brief clinical interview with the second author, a qualified clinical psychologist, report no history of an ED themselves. They were recruited through advertising in the local community in public places including libraries and coffee shops. The aim was to represent a range of age groups, with participants sought from the 18-24 and 40-55 age groups, such that the two quasi-experimental groups would be stratified by age. Participants were required to be able to provide informed consent and to have a sufficient command of the English language to enable participation in a face-to-face interview.

Procedure

Participants interested in taking part were asked to approach the researcher who provided an information sheet and was able to answer any questions about the study. If the participant then wished to take part, written informed consent was collected. An appointment was scheduled to hold the interview.

An interview schedule consisting of 10 semi-structured questions was developed based on a thorough evaluation of literature, consultation with experts in the field and refined after a pilot stage. The questions included the following: “when I say the word “eating disorder”, what do you think of? Can you tell me what you think an eating disorder is? How or why do you think eating disorders may develop? How serious do you think eating disorders are? If you imagine a person with an eating disorder, what would your attitude be towards them? (For example, how would you feel towards them, what would you think about them and how would you behave around them?”. The questions were posed in an individual, face-to-face context to all female participants in a quiet setting in the University using a voice recorder to record each interview. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time. Information about ED support services were provided to all participants and a full debrief was given at the end of the interview. All interviews were transcribed and pseudonyms are used to protect participants’ identities.

The study received ethical approval from the Regent’s University London Research Ethics Committee Ref. 14.04 and was conducted in line with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed and analysed using Thematic Analysis [35], a technique used to analyse qualitative data through distilling themes and disseminating findings and has been used in other studies exploring EDs [36]. Thematic analysis was considered suitable given its flexibility, theoretical freedom and its descriptive rather than interpretative function, making it preferable to other methods, such as Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis [37] and Grounded Theory [38]. Whilst IPA focusses on detailed systematic interpretation of personal experience and Grounded Theory uses theoretical sampling to develop a theoretical explanation, thematic analysis focuses on the description of divergence and convergence of experiences [35]. In keeping with this approach, a hybrid process of inductive and deductive thematic analysis of raw data was utilised, such that some themes were identified from the data whilst others, given previous literature, were hypothesised a priori. Validation processes and reliability standards for the conduct of high quality qualitative research [39,40] were followed. Triangulation, a method commonly employed in qualitative research to corroborate findings to increase reliability and validity of results, ensuring that accounts are rich, robust and comprehensive was pursued by combining different sources of information (e.g. understanding the research question from multiple perspectives) and through holding regular joint discussions between the researchers regarding emerging themes and via co-author (AH) co-analysing a 20% subsample of the data. A reflective diary was also maintained to ensure transparency and credibility of the themes identified; the master table of themes was continuously updated throughout analysis; the identification and inclusion of contradictory or negative cases and accounts were sought; participant theme validation was pursued through offering participants transcripts and drafts of the thematic analysis throughout the preparation of the report; and the findings of the research were presented to an audience of professionals, patients and carers at the Eating Disorders International Conference in London in March 2016. In line with this type of qualitative approach, a reflective summary is provided at the end of the discussion. In the first stage of analysis, the two authors independently read the transcribed material and made notes concerning the main issues they felt were present in the data. Next, they met to discuss their views and to develop a coding scheme and subsequently, the first author coded each contribution. The authors met once again to discuss the codes and to collapse them into themes discussed in the results section. The full sample of transcripts was assessed to develop the themes and then further exploration was conducted to identify possible differences between the experienced and inexperienced participants.

Reflexivity

The first author of this study is a white British woman, studying psychology at undergraduate level. She also works voluntarily for a charity which supports people affected by EDs. The second author is a white British woman who currently works as a clinical psychologist with young people with severe EDs and is a lecturer in psychology. She has been involved in working clinically with people with EDs and in conducting research into EDs for 9 years. During the analysis, regular meetings were held, during which authors discussed the emerging themes, and reflected on how their backgrounds and beliefs might impact on their interpretation of data.

Results

The final sample consisted of 20 female participants with a mean age of 35.55 (SD=15.91). The groups were similar in age (t=1.235, df=1, p=0.901) and the stratification approach appeared to be successful, as participants’ ages were well distributed within the two groups, demonstrated in Table 1.

| Pseudonym | Age | Experience | Summary of Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kylie | 20 | Yes | Kylie’s sister was diagnosed with an eating disorder when Kylie was 11 and her sister was 14. Her sister was treated as an impatient at the age of 17 and is working towards recovery. |

| Chloe | 23 | Yes | Chloe had two close school friends that suffered with anorexia and bulimia, one of which she still remains very close with. |

| Emmy | 20 | Yes | Emmy’s cousin suffered with anorexia and bulimia and was treated as an impatient at a clinic. She was very close with her cousin and still remains close with her. |

| Louise | 21 | Yes | Louise’s sister has suffered with anorexia and bulimia for the past 12 years. Her sister has been in and out of hospital and care homes in past 12 years and still battles with an eating disorder. |

| Leanne | 22 | Yes | One of Leanne’s best friends suffered with an eating disorder, which she found very difficult to understand. |

| Kelly | 48 | Yes | Kelly’s goddaughter suffers with anorexia and has been treated as an impatient in the past, however still suffers quite severely. |

| Gina | 55 | Yes | Gina’s niece suffers with anorexia and bulimia |

| Sally | 49 | Yes | Sally’s close friend suffered with anorexia, and still suffers to an extent. Sally also has a family member who suffers with binge eating disorder. |

| Carol | 49 | Yes | Carol’s daughter was 15 when she was diagnosed with bulimia, and was treated for anorexia when she was 17. Carol found it something she had to get her head round very quickly, and it was something that affected the whole family. |

| Dianna | 48 | Yes | Dianna has a close friend with an eating disorder. |

| Annie | 23 | No | Annie new of a few girls at college that suffered with an eating disorder however, has never been close to anyone affected. |

| Eve | 20 | No | Eve has known of a girl (a friend of her sister) who has suffered with an eating disorder, but has never been close to anyone affected. |

| Harriet | 20 | No | Harriet’s friend’s sister suffered with an eating disorder, but it was never discussed. Harriet has not come across any other individuals that have suffered with an eating disorder. |

| Hayley | 20 | No | Hayley knew of a girl who suffered with an eating disorder but has not had anyone close to her suffer. |

| Jenny | 20 | No | Jenny has never been close to anyone that has suffered with an eating disorder. |

| Debbie | 49 | No | Debbie has never known anyone who has suffered with an eating disorder. |

| Penny | 51 | No | Penny has been aware that a few of her friend’s daughter that have suffered but has had no personal experience herself. |

| Darcy | 51 | No | Darcy’s friend’s daughter suffered with an eating disorder but she was not aware of what went on. |

| Sarah | 54 | No | Sarah knows of a friend whose daughter suffers but has not had contact with this person, nor any other personal experience. |

| Whitney | 48 | No | Whitney’s friend’s daughter suffered with an eating disorder but she did not have any contact with this individual and it was seldom discussed. |

Table 1: Participant Demographics and Eating Disorder Experience.

The themes were partly shaped by the interview questions and partly emerged from the data. Thematic analysis resulted in four key themes: understanding the illness, nature of the illness, triggers and hope and the future. These key themes were comprised of several subordinate themes: three in understanding the illness, four in nature of the illness, five in triggers and three in hope and the future. The key themes were discussed by all participants and as highlighted below, the content of the subordinate themes frequently differed when discussed by experienced and inexperienced participants. The following section will present the key themes and use transcripts excerpts to illustrate the subthemes.

This theme related to levels of education around EDs of different parties and the possible consequences of low levels of education. The subordinate themes reflect these stakeholders and included general practitioners (GPs), (with a consequence being the additional sub-theme of funding issues), society, and the participant’s own understanding. Experienced participants tended to highlight the poor education they had encountered and inexperienced participants tended to emphasise their own poor education (Figure 1).

Carol (Experienced): “When I first found out I took her to our GP, and as lovely as she was, she didn’t really have a clue what to suggest. When my daughter started with bulimia, her BMI (body mass index) wasn’t low enough to indicate significant weight”

Louise (Experienced): “My mum wasn’t actually able to get funding, and this is a serious mental illness. It was really expensive, but obviously she was just so ill that it’s something my mum had to find the money”

Leanne (Experienced): “I know people who have experienced it and I still feel like I don’t understand it enough. I feel like it is so difficult for everyone to get their head round…”

Kelly (Experienced): “I really think an eating disorder is something that requires a lot more understanding… I don’t think people realise that they are mental illnesses’’ Conversely, inexperienced participants focused more on their own experiences of confusion towards the illness and a lack of understanding regarding their categorisation as mental illnesses.

Penny (Inexperienced): “Quite honestly I don’t really understand eating disorders; they all seem like a horrible waste of time for the person. I think they are mental illnesses, but I’m not sure”

Hayley (Inexperienced): “I find eating disorders impossible to understand-I can’t really get my head around why someone would stop eating. When you mentioned the words ‘eating disorder,’ the first thing I think of is someone not eating, and so I don’t really think about mental illness”

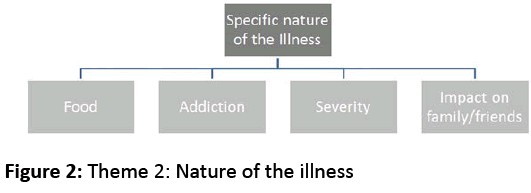

The second theme reflected participant’s ideas about the nature of the illness and subordinate themes related to the role of food, the illness as an addiction, awareness of the possible severity of the illness and the broader impact of the illness on friends and family members. The role of food was an important subordinate theme discussed in each participant’s interview and tended to be conceptualised as a maintaining factor of the illness. Experienced participants recognised that an ED often has a number of functions, roles, and forms (Figure 2).

Gina (Experienced): “I appreciate that it isn’t just about food – it’s also about other things like control, emotions, womanhood, anxiety, so many things.” Conversely, four inexperienced participants used the phrase ‘why don’t they just eat?’ focusing more strongly on the illness being about food only.

Annie (Inexperienced): “I think the clue is in the title, it is an ‘eating disorder’ so yes it is all to do with eating or not eating.” The subordinate theme of addiction was discussed primarily by experienced participants and related to their own process of making sense of the illness.

Dianna (Experienced): “It just seemed like she couldn’t stopthe starvation-it was like she had to keep getting that hit. It was scary, she really couldn’t stop”. This was a topic that was frequently linked to treatment. For example, one experienced participant questioned why she felt other addictions were more easily attended to in comparison to EDs.

Carol (Experienced): “It’s like an addiction. Alcoholics are treated, drug addicts are treated, and there is an abundance of help for them and there is not that kind of help for people with eating disorders.” The subordinate theme of severity was endorsed by all participants who recognised the severity of the illness, acknowledging that in severe cases, EDs can be life threatening.

Kylie (Experienced) and Eve (Inexperienced): You can die from an eating disorder”. The fourth subordinate theme was the impact of the illness on friends and family of the sufferer. It was clear from the participants who had been close to a sufferer that they identified EDs as illnesses which impacted a broad network.

Emmy (Experienced): “What the whole family went through, I wouldn’t wish anyone to go through because it does have such a negative effect on the family as well, and I know that my other cousin (her sister) found it so difficult when she went away to the clinic”. This sub theme was not endorsed by the inexperienced participants.

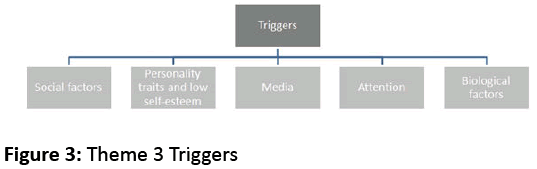

All participants discussed factors they believed cause EDs. The relative influences of biological and social factors were important subordinate themes in which there were striking differences between the experienced and inexperienced participants. All inexperienced participants reported that they had not considered biological factors as a trigger, nor did they think they were particularly relevant, further justifying that this was due to lack of knowledge regarding biological factors (Figure 3).

Jenny (Inexperienced): “I understood the causes to be more related to celebrity culture and the pressure women are under. I haven’t thought about genes or anything like that before.” Conversely, a number of experienced participants discussed a biological basis for the illness, with ideas expressed around the illness being triggered by a genetic predisposition.

Dianna (Experienced): “I do know that our genetics can give us a predisposition, to sort of being anxious, or a worrier, nervous person, and I think it can manifest itself in different ways, possibly in an eating disorder.” In the subordinate theme of attention, inexperienced participants tended to endorse this idea more strongly than experienced participants.

Sarah (Inexperienced): “ I think if you go back for treatment three times then it is attention seeking, I mean I know quite a few people that would just say it’s attention seeking, I think maybe if the person doesn’t have the limelight anymore then that might be their way of grabbing it.” The sub theme of attention was endorsed differently by the experienced participants, with participants expressing the idea that being unwell might inadvertently offer the person attention and that it may not actually be wanted.

Louise (Experienced): “I know some people might think they do if for attention, but I don’t agree. If anything, people want to hide away and not be seen, although people do pay you more attention when you’re ill, particularly when you’re starving to death, but the person may not want it. People stare at them sometimes and I know they don’t like that.” The subordinate theme of personality traits and self-esteem was discussed by both experienced and inexperienced participants, with points made by both groups around low self-esteem and low selfworth, alongside high levels of control and perfectionism being causes of EDs.

Sally (Experienced): “I think if you’re suffering, your selfworth levels are very low… I suppose food is almost a mechanism for what they can control but I think it is very much an emotional thing.”

Debbie (Inexperienced): “I do get the sense from what I have read that eating disorders are caused by low self-esteem and people wanting to do things perfectly and feel in control.”

The final subordinate theme related to the perceived influence of the media on the development of EDs and this was the most strongly opinionated theme discussed throughout all of the interviews with both experienced and inexperienced participants. With the exception of one experienced participant, participants appeared to be in agreement that the media has a huge role to play in the development and maintenance of an ED. Ideas expressed relating to blaming runway models, magazines and the Internet. A typical viewpoint was as follows:

Sally (Experienced): “I think the media has an awful lot to answer for… There is just very little out there these days that gives us a ‘normal’ image or the right positive message to younger girls especially, and the fashion industry are always promoting very thin girls.”

One experienced participant had a rather different opinion regarding the perceived role of the media.

Louise (Experienced): “I think this whole blaming it on the Internet and the media, is kind of a load of rubbish, because all these models on the runway that is their body types, some people are naturally slim. People may want to look like models and might lose weight and try to look like them and they don’t all get eating disorders. I would never say that the media and the way models look would be the cause of anorexia and bulimia.”

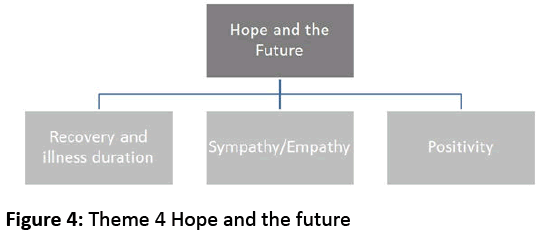

This key theme related to ideas expressed around hope and the future in the context of recovering from the illness. There were apparent differences between participants with and without experience of EDs concerning the subordinate theme of the possible duration of an ED. Although the majority of participants recognised that EDs might have a lifelong impact on an individual, inexperienced participants estimated that it would take a sufferer anything from 18 months to 4 years to recover, whereas experienced participants discussed how people should be prepared for a lifelong battle with the ED. Most participants acknowledged that recovery is possible, however the experienced participants elaborated more on the idea that EDs are difficult to overcome, perhaps suggesting greater empathy than inexperienced participants (Figure 4).

Carol (Experienced): “I think it can be manageable, but I think that once you have an eating disorder, once it gets hold of you, it becomes a lifetime maintenance program.”

Leanne (Experienced): “it lasts for longer than people think, I think even when you recover, there’ always going to be that tiny thing in your head that I would imagine doesn’t ever go away. Therefore, I’m not sure you’d ever be able to say ‘I’ve had an eating disorder and I don’t even think about it anymore”.

Harriet (Inexperienced): “I do get the sense that eating disorders last a long time but I think people can fully recover and never worry about food again. I don’t know for how many people this would be the case, but I think it could take around 3 or 4 years to recover completely from it.”

The subordinate theme of sympathy was expressed towards sufferers throughout the interviews by both experienced and inexperienced participants.

Harriet (Inexperienced): “I don’t think I would act differently around them, I would just feel really sorry for them.”

Chloe (Experienced): “It’s such a horrible illness – you wouldn’t wish it on your worst enemy.”

A final subordinate theme was positivity. Participants articulated mixed views around this subordinate theme, with experienced participants tending to discuss positive attributes such as greater strength being derived from overcoming the illness.

Kylie (Experienced): “I think it’s such a big thing to overcome, and it can make you a stronger person and appreciate life more… the change in my sister is rather big...I know she tries to be a lot more positive now in everyday life…”

Chloe (Experienced): “I think it is a massive achievement, you know, to be able to fight…I mean to me that person has come out stronger.”

There was also the sense that those who have experienced EDs could educate the rest of the public about the illness because of their experiences and that this would be a positive outcome in terms of being a benefit to society.

Chloe (Experienced): “I think if that person wishes to, he or she could really help society understand what it is like to go through something like this… they can educate friends, and help people understand more about eating disorders. I think making it more known and more talked about would be good for society.”

On the other hand, inexperienced participants felt that the only positive outcome of an ED would be in overcoming it. Contrary to the experienced participants, inexperienced participants felt there could be absolutely no positives derived from the experience of an ED.

Whitney (Inexperienced): “I really can’t imagine it would be a positive thing in any way for anybody.”

Discussion

This qualitative study had two aims: To enhance the evidence base regarding public education around EDs with the objective of highlighting the need for well-funded public education programmes around EDs and, through interviewing experienced and inexperienced participants, to explore whether contact with those with EDs improves ED-related education. Thematic analysis yielded four key themes and this section will discuss the themes in the context of the research question: to what extent do the public needs educating about EDs?

The first key theme was levels of education about the illness itself, with participants discussing their own levels of education, as well as that of GPs’ and society more broadly. Experienced participants tended to report possessing greater education around EDs than inexperienced participants who endorsed a lack of education. The lack of education was also highlighted through experienced participants’ accounts of GP appointments, who reportedly misunderstood the seriousness of EDs, mirroring previous research involving GPs [17,40]. These findings, alongside comments from both participant groups relating to poor education around EDs across the general population, support the need for public education programmes for EDs.

The second key theme reflected education around the specific nature of EDs. There were a number of subordinate themes in this category. The role of food was a central subtheme and inexperienced participants endorsed the notion that the illness was entirely food-related. Experienced participants, however, discussed a range of possible maintaining factors, knowledge more in keeping with published literature [23]. A second subtheme related to EDs as addictions and was primarily endorsed by experienced participants who questioned why other addictions offered successful treatment programmes, whereas they felt EDs did not. The third subtheme was illness severity and all participants highlighted that EDs may last a long time, reflecting improved education in contrast to previous research [7], although experienced participants’ estimations of duration were accurate and reflected the reported average of eight years [41] and experienced participants were more aware, as highlighted in the literature, that EDs may take a severe and enduring course [42]. The third subtheme was how the illness impacts friends and family. Experienced participants talked extensively about the effect of EDs on friends and family, mirroring published literature [23], whereas this was not an aspect of the illness that inexperienced participants were aware of.

In the third key theme, illness etiology, a range of causes were posited. The experienced group demonstrated greater awareness of the biological basis of EDs than the inexperienced group, demonstrating knowledge more in keeping with published literature [3] and some experienced participants reflected that if the media acted as the key trigger, EDs would be more prevalent, accurately reflecting published literature [43]. Conversely, mirroring previous findings [7-8], the inexperienced group tended to implicate ‘attention seeking’ and the media as key causal factors and had not considered the role of genetic factors. Furthermore, there was awareness, particularly amongst experienced participants, that low self-esteem and criticism may be important etiological factors, corroborating published literature regarding the range of putative risk factors [44]. However, clear detail and depth were absent across both groups which highlights the need for public education programmes which disseminate known information about ED risk factors. A possible consequence of the current degree of knowledge reported by, particularly inexperienced participants, might be reduced prevention and detection and therefore the current situation may represent a significant threat to the ability of health services to reduce the prevalence of EDs.

The fourth key theme was hope and the future, with both groups demonstrating some awareness of the challenges of recovery. The experienced participants in particular endorsed knowledge regarding the level of effort required to fight the illness. Interestingly, inexperienced participants discussed a finite course for the disorder, whereas the experienced participants felt that an ED would remain with an individual in some capacity forever. However, while inexperienced participants were not aware of the personal development that may come from overcoming the illness, experienced participants were, and they discussed the positive role of recovered individuals in supporting others and in keeping with published literature, unlike inexperienced participants, they were aware that friends and family are a vital resource in recovery [26]. This further highlights the need for better education, as a lack of knowledge regarding the usefulness of friends and family in recovery may reduce opportunities for the public to offer support. Both groups offered sympathy towards people with EDs, although, perhaps because of their improved education, the experienced participants offered greater empathy. The sympathy and empathy offered by all participants is in contrast to prior studies [34] and future work may wish to further explore whether sympathy and empathy towards those with EDs are improving amongst the public.

The rich and in-depth data obtained from this study highlight levels of education around EDs reported by female participants with different degrees of ED experience. The analysis used allowed personal opinions and experiences to be communicated and understood in terms of the four key themes outlined above. In contrast to previous research [8-11,34], strong negative views were not heavily endorsed, although the lack of education amongst the inexperienced participants may have led them to erroneously consider EDs as having an attention seeking function and being solely about food. In spite of the experience of some of the participants, the interviews highlighted a lack of accurate, in-depth education regarding all aspects of EDs, suggesting that strong, accurate knowledge around EDs in the public is present to a limited extent and well-funded public education programmes are warranted to improve this.

The study has a number of limitations. It did not include male participants and future work should address this. The sample was recruited using convenience sampling which may have led to bias in the data. This was an adult sample and given the typical adolescent onset of EDs, future work could involve younger cohorts who may be close friends with other adolescents with EDs.

In conclusion, given the gaps in knowledge observed, this work provides further support for initiatives promoting collaboration with the friends and family members of people with EDs which have a strong educational component [26] and highlights that well-funded public education campaigns, successfully offered in relation to schizophrenia [30-33], are needed for EDs, as clearly experience alone can only provide this knowledge and understanding to a limited population. Such a programme may wish to begin by targeting the themes of understanding salient to participants in this study; i.e. general and specific knowledge, education around aetiological factors, negative attitudes regarding the function of the illness, possible illness outcomes and ways to improve empathy.

References

- Klump KL, Bulik CM, Kaye WH, Treasure J, Tyson E (2009) Academy for Eating Disorders position paper: Eating disorders are serious mental illnesses. Int J Eat Disord42: 97-103.

- Schmidt U (2009) Cognitive behavioural approaches in adolescent anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Child Adol PsychCl 8: 147-158.

- Collier DA, Treasure JL (2004) The aetiology of eating disorders.British J Psychiat185: 363-365.

- Brandys MK, de Kovel CG, KasMJ, van Elberg AA, Adan RA (2015) Overview ofgeneticresearch in anorexia nervosa: The past, the present and the future. Int J Eat Disord 48: 814-825.

- Klump KL,SuismanJL,Burt SA, McGue M, IaconoWG (2009) Genetic and environmental influences on disordered eating: An adoption study.J Abnorm Psych 118: 797-805.

- Boraska V,Franklin CS,Floyd JA, Thornton LM,Huckins LM, et al. (2014) A genome-wide association study of anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatr 19: 1085-1094.

- Bulik C(2004) Genetic and biological risk factors. In: Thompson KJ(edt). Handbook of Eating Disorders and Obesity. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 3-16.

- Easter MM (2012) “Not all my fault”: Genetics, stigma, and personal responsibility for women with eating disorders. SocSci Med 75: 1408-1416.

- MondJM, Robertson-Smith G, Vetere A (2006) Stigma and eating disorders: Is there evidence of negative attitudes towards anorexia nervosa among women in the community? J Ment Health 15: 519-532.

- Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, Meltzer HI, RowlandsOJ (2000) Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. Brit J Psychiatr 177: 4-7.

- Roehrig JP, McLean CP (2010) A comparison of stigma toward eating disorders versus depression. Int J Eat Disord 43: 671-674.

- Stewart MC, Keel PK, Schiavo RS (2006) Stigmatization of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 39: 320-325.

- Stuart H, Arboleda-Flórez J (2012) A Public Health Perspective on the Stigmatization of Mental Illnesses. Public Health Rev 34: 1-18.

- Rabkin JG (1974) Public attitudes toward mental illness: a review of the literature.Psychol Bull 10: 9-33.

- Bhugra D (1989) Attitudes toward mental illness: a review of the literature.ActaPsychiatScand 80: 1-12.

- Stewart MC, Schiavo RS, Herzog DB, Franko DL (2008) Stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination of women with anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 16: 311-318.

- Hay PJ, de Angelis C, Millar H, Mond J (2005) Bulimia nervosa mental health literacy of general practitioners. Primary Care Commun 10: 103-108.

- Jones WR, Saeidi S, Morgan JF (2013) Knowledge and Attitudes of Psychiatrists towards Eating Disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 21: 84-88.

- Hackler AH, Vogel DL, Wade NG (2010) Attitudes toward seeking professional help for an eating disorder: the role of stigma and anticipated outcomes. J CounsDev 88: 424-431.

- Becker AE, Franko DL, Nussbaum K, Herzog DB (2004) Secondary prevention for eating disorders: The impact of education, screening, and referral in a college-based screening program. Int J Eat Disord 36: 157-162.

- Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH (2006) Help seeking and barriers to treatment in a community sample of Mexican American and European American women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 39: 154-161.

- Striegel-Moore RH, Leslie D, Petrill SA, Garvin V, Rosenheck RA (2000) One-year use and cost of inpatient and outpatient services among female and male patients with an eating disorder: evidence from a national database of health insurance claims.Int J Eat Disord27: 381-389.

- Schmidt U, Treasure J (2006) Anorexia nervosa: Valued and visible. A cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. Brit J ClinPsychol 45: 343-366.

- Corrigan P (1998) The impact of stigma on severe mental illness. Cog BehavPract 5: 201-022.

- Scheff T (1966) Being Mentally Ill: A Sociological Theory. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company. 210 p.

- Treasure J, Rhind C, Macdonald P, Todd G (2015) Collaborative care: The new Maudsley model. Eat Disord 3: 336-376.

- Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, McLean SA, Massey R, Mond J, et al. (2015) Stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs toward bulimia nervosa: The importance of knowledge and eating disorder symptoms. J NervMent Dis 203: 259-263.

- Holmes EP, Corrigan PW, Williams P, Canar J, Kubiak MA (1999) Changing attitudes about schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull 25: 447-456.

- Corrigan PW, Edwards AB, Green A, Diwan SL, Penn DL (2001) Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bull 27: 219-225.

- Thompson AH, Stuart H, Bland RC, Arboleda-Florez J, Warner R, et al. (2002) Attitudes about schizophrenia from the pilot site of the WPA worldwide campaign against the stigma of schizophrenia. SocPsychiat Psychiatric Epidem 37: 475-482.

- Morrison JK, CocozzaJJ, Vanderwyst D (1980) An attempt to change the negative, stigmatizing image of mental patients through brief re-education. Psychol Rep 47: 334.

- Penn DL, Guynan K, Daily T, Spaulding WD, GarbinCP, et al. (1994) Dispelling the stigma of schizophrenia: what sort of information is best? Schizophrenia Bull 20: 567-578.

- Griffiths S, MondJM, Murray SB,Toyez S (2014) Young peoples’ stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs about anorexia nervosa and muscle dysmorphia. Int J Eat Disord 47: 187-195.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3: 77-101.

- Tierney S, Fox JR (2010) Living with the anorexic voice: A thematic analysis. PsycholPsychother 83: 243-254.

- Smith JA, Osborn M (2003) Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Smith, editor. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods. London: Sage. pp 53-80.

- Glaser B, Strauss A (1967) The discovery grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative inquiry. Chicago: Aldine Transaction. 271 p.

- Henwood KL, Pidgeon NF (1992) Qualitative research and psychological theorizing. Br J Psychol 83: 97-111.

- Elliott R, Fischer CT, Rennie DL (1999) Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. Br J ClinPsychol 38: 215-229

- Currin L, Waller G, Schmidt U (2009) Primary care physicians’ knowledge of and attitudes toward the eating disorders: Do they affect clinical actions? Int J Eat Disord 42: 453-458.

- Hay P, Chinn D, Forbes D, Madden S, Newton R, et al. (2014) Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Aust NZ J Psychiat 48: 977-1008.

- Arkell J, Robinson P (2008) A pilot case series using qualitative and quantitative methods: Biological, psychological and social outcome in severe and enduring eating disorder (anorexia nervosa). Int J Eat Disord 41: 650-656.

- Levine MK (2009) “Everybody knows that mass media are/are not [pick one] a cause of eating disorders”. A critical review of evidence for a causal link between media, negative body image, and disordered eating in females. J SocClinPsychol 28: 9-42.

- Jacobi C, Fittig E, Bryson SW, Wilfley D, Kraemer HC, et al. (2011) Who is really at risk? Identifying risk factors for subthreshold and full syndrome eatingdisorders in a high-risk sample.Psych Med 41: 1939-1949.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences