Extreme Obesity and its Associations with Victimization, PTSD, Major Depression and Eating Disorders in a National Sample of Women

Timothy D Brewerton, Patrick M ONeil, Bonnie S Dansky, Dean G Kilpatrick

DOI10.21767/2471-8203.100010

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC 29425

- *Corresponding Author:

- imothy D Brewerton

Timothy D Brewerton, MD “216 Scott St., Mt. Pleasant, SC 29464-4345.

Tel: 843-509-0694

E-mail: drtimothybrewerton@gmail.com

Received Date: October 13, 2015; Accepted Date: November 18, 2015; Published Date: November 21, 2015

Citation: Timothy DB,Patrick MO,Bonnie SD,Kilpatrick DG (2016) Extreme Obesity and its Associations with Victimization, PTSD, Major Depression and Eating Disorders in a National Sample of Women: The Controlled Overeat. J Obes Eat Disord 1:10. doi: 10.4172/2471-8203.100010

Copyright: © 2016, Timothy DB et al, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Crime victimization experiences, such as rape, molestation, and aggravated assault are significantly associated with bulimia nervosa (BN) and associated psychiatric comorbidity such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and substance abuse. Obesity also appears to be a major risk factor for the development of BN, but few studies have examined the relationship of crime victimization experiences to obesity and related psychopathology.

Introduction

We have previously reported that crime victimization experiences, such as rape, molestation, and aggravated assault are each significantly associated with bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating, purging behaviors, as well as associated psychiatric comorbidity such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and substance abuse [1-7]. Obesity has also been noted by several clinical investigators to be a major risk factor for the development of BN and disordered eating behaviors [8,9].

Several investigators have reported an association between obesity and prior traumatic victimization. Felitti reported that a high number of patients who failed a weight control program gave a clear-cut history of childhood sexual abuse [10,11]. He studied 131 patients with a history of incest, molestation, and/ or childhood rape and age‑ and sex‑matched controls from the same general medical population and found higher rates of chronic depression, extreme obesity (EO), marital instability, and a high utilization of medical care. Kanter reported that 62 obese males and 274 females with binge eating who were seeking obesity treatments had greater rates than obese non-binge eaters of alcohol abuse, parental alcohol abuse, and victimization experiences including physical and sexual abuse [12]. Using a very large data set (n=13,494) in which Kaiser Health Plan members completed standardized medical evaluations (the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE study)), Felitti and colleagues noted that obese patients reported more childhood sexual abuse, nonsexual childhood abuse, early parental loss, parental alcoholism, depression, and marital and family dysfunction than non-obese patients. Adverse childhood exposure was associated with an increased lifetime risk of severe obesity defined by these investigators as BMI ≥ 35. Individuals who had experienced four or more categories of childhood exposure compared to those who had experienced none had a four‑ to twelve-fold increase health risk for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempts and a 1.4‑ to 1.6‑fold increased risk for physical inactivity and severe obesity [13]. Other investigators have confirmed the link between victimization histories and obesity [14-20]. In the large California Health Study (n=11,115), Alvarez and co-investigators found that obese women were found to have significantly higher rates of reported child abuse (defined as experiencing either physical or sexual abuse before age 18) [14]. In a population-based survey of women enrolled in a Pacific Northwest health plan (n=4641), Rohde and colleagues found that both childhood sexual and physical abuse were associated with significantly higher rates of both obesity (OR: 2.8) and depression (OR: 2.2) [18]. Aaron and Hughes reported that lesbian women who reported childhood sexual abuse were more likely to be obese (OR: 1.9) or extremely obese (OR: 2.3) [21]. In a prospective, longitudinal study, Noll and colleagues reported that sexually abused girls were more likely to become obese by young adulthood [17]. In another prospective, longitudinal study, Bentley and Widom found that only childhood physical abuse, but not childhood sexual abuse or neglect, predicted higher BMI scores 30 years later [15]. However, the authors noted a relatively small sample of sexually abused girls as a possible explanation for their negative results. Finally, Sansone and associates reported high rates of childhood trauma in a series of patients (86% women) with EO seeking bariatric surgery [19]. In addition to the published links between obesity and prior victimization, there have also been reports revealing links between obesity and PTSD [22-25]. Given that trauma is not simply the occurrence of an adverse event, but also includes the individual’s experience of the event as well as the effects of the event (the three “e’s”), it is imperative to also consider the emergence of PTSD and PTSD symptoms in assessing the long-term impact of trauma [3,6,26]. PTSD and partial PTSD (pPTSD) are more powerful predictors of bulimic EDs and other related psychiatric comorbidity than the traumatic event(s) alone [2-6,27,28].

Obesity has also been reported to be associated with MDD and other mood disorders, while findings regarding its links to alcohol use/dependence are mixed [29,30]. However, the links between alcohol use/dependence with PTSD, BN, bingeing and purging are stronger [2,6,31,32].

Given these relationships we hypothesized that obesity, and specifically EO, would be associated with prior crime victimization and related psychiatric comorbidity in this representative sample of women from across the United States. Since the focus of this study was to assess the association of degrees of lifetime overweight and obesity with victimization and psychiatric comorbidity, maximum BMI was used as opposed to current BMI.

Methods

Sample

The original sample of 4,009 women was generated by multistage geographic sampling involving random-digit dialing. Subjects completed a telephone interview lasting on average forty minutes. The completion rate for Wave 1 was 85.2%, and 75% of Wave 1 sample completed Wave 3 approximately two years later (1992), leaving a national sample of 3,006 women participating in this anonymous survey.

Instruments

Behaviorally-specific questions about DSM-IV defined PTSD Criterion A events were asked of all participants and included forcible rape, sexual molestation, attempted sexual assault, aggravated assault, and surviving homicide. In addition, the evaluation of BN, binge eating disorder (BED), PTSD, substance abuse and dependence, and MDD was based on structured interview using DSM‑III‑R criteria, which was later modified for DSM-IV. [33] The details of these studies have been previously described elsewhere [1,2,4,28,34,35].

As part of the PTSD assessment all respondents were asked about a lifetime history of forgetting all or parts of experiences (amnesia) using the following question: "Throughout this interview we've talked about distressing experiences that you have had. Have you EVER felt that there were parts of any experience that you couldn't remember?" Immediately following this question, all respondents were then asked whether this had happened recently: "During the last month, have you felt that there were parts of any such experience that you couldn't remember?" Affirmative responses were categorized respectively as having "amnesia," lifetime and current [28].

During the course of the interview subjects provided selfreported height and weight, which was used to calculate current BMI as well as maximum and minimum BMI’s during adulthood. Subjects’ maximum lifetime BMI’s were categorized into five groups: 1) less than 25, 2) 25 to less than 30, 3) 30 to less than 35, 4) 35 to less than 40, 5) ≥ 40 using standard cutoff points [36]. Childhood BMI was not assessed.

Statistics

The General Linear Model (GLM) univariate procedure of SPSS 21.0 was used to perform regression analysis and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for relevant dependent variables. This procedure determined whether significant differences existed in the prevalence of rape, molestation, aggravated assault, attempted sexual assault, surviving homicide, current and lifetime PTSD, current and lifetime MD, lifetime bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, and drug use using BMI category as the grouping variable. Since the Wave 3 sample was collected in 1992, the data were weighted according to estimates of the 1992 United States (US) census figures for age and race. The weighting program was used to ensure that sample data were representative of women in the US population. In addition, post‑hoc Bonferroni t‑tests were used for betweencell comparisons when the t‑value of the ANOVA met clinical significance. The sample sizes, mean weighted ages, and racial distribution of the sample are provided in Table 1. There was no significant difference in average income across the BMI groups.

| Variable | <25 | 25-<30 | 30-<35 | 35-<40 | >40 | F or χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 1404 | 803 | 425 | 188 | 123 | |

| Age | 38.6 + 15.8a | 44.8 + 17.6b | 45.2 + 17.7b | 43.7 + 16.3b | 41.5 + 13.6a | 24.8*** |

| Race | 3.1* | |||||

| % Black | 6.7% | 8.0% | 8.0% | 8.0% | 8.0% | |

| % White | 88.4% | 88.5% | 88.5% | 88.5% | 88.5% | |

| % Asian | 1.9% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | |

| % Native American | 2.7% | 1.9% | 1.9% | 1.9% | 1.9% | |

| % Pacific Is. | 0.4% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.9% |

Table 1 Sample sizes and demographic characteristics of the sample by maximum BMI group. ***p<0.001, ANOVA; * p<0.05, χ2. Significant differences between groups as per post-hoc Bonferroni t-tests (p<0.05) are indicated by different letters in subscript.

Results

A summary of the results are presented in Table 2, which includes population weighted means and standard deviations by maximum BMI group. The average age at maximum BMI was 32.8 ± 13.1 years as compared to the average age at the time of assessment (35.9 ± 15.4 years), an average difference of 3.2 ± 9.0 years (paired t-test, t=18.8, p ≤ 0.001). Maximum BMI was highly correlated with current BMI (r=0.88, p ≤ 0.001).

| Variable | <25 | 25-<30 | 30-<35 | 35-<40 | >40 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

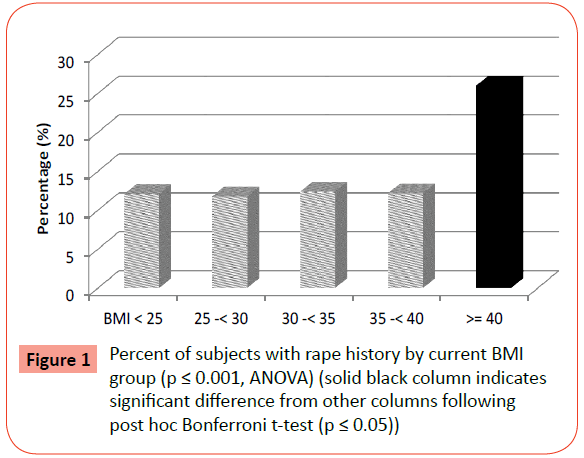

| Rape | 12.1 ± 30.9a | 11.8 ± 33.2 a | 12.4 ± 35.2 a | 12.2 ± 34.0 a | 26.0 ± 46.6b | 5.88*** |

| Molestation | 5.6 ± 20.8 | 3.8 ± 19.8 | 5.8 ± 24.9 | 3.5 ± 19.1 | 5.6 ± 24.4 | 0.99 |

| Attempted SA | 10.2 ± 30.3 | 9.0 ± 28.6 | 10.8 ± 31.1 | 9.0 ± 28.8 | 15.5 ± 36.3 | 1.38 |

| Physical Assault | 10.8± 29.4 | 8.9 ± 29.4 | 10.7 ± 33.1 | 8.3 ± 28.8 | 11.0 ± 33.2 | 0.78 |

| Homicide Survivor | 14.6 ± 33.5a | 11.7 ± 33.1a | 14.6 ± 37.7a | 15.6 ± 37.8a | 22.0 ± 44.2a | 3.0* |

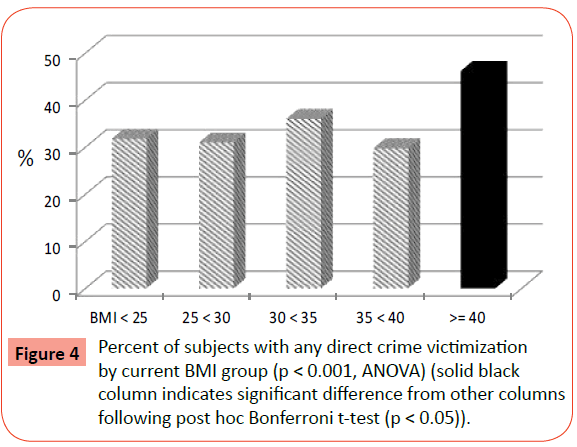

| Any DCV | 31.8 ± 44.1a | 31.0 ± 47.8a | 36.0 ± 51.3a | 29.8 ± 47.6a | 46.2 ± 53.0b | 4.02** |

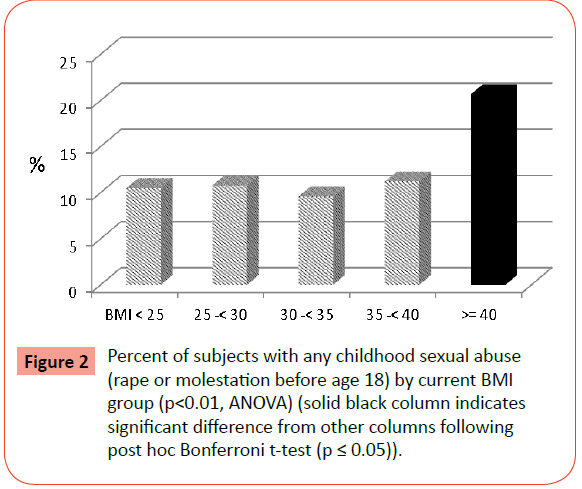

| Any CSA | 10.5 ± 29.1a | 10.8 ± 32.1a | 9.6 ± 31.4a | 11.2 ± 32.8a | 20.7 ± 43.0b | 3.65** |

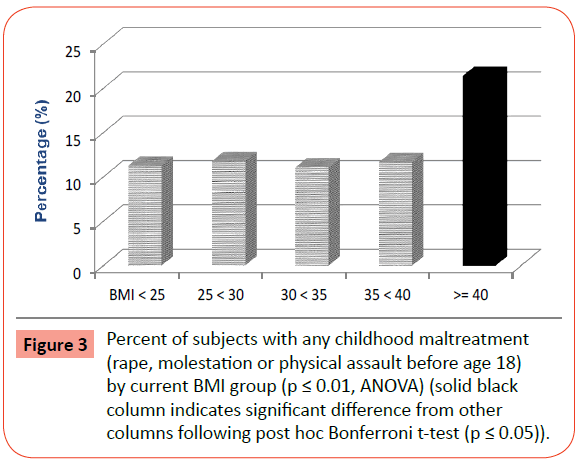

| Any CA | 11.3 ± 30.1a | 11.8 ± 33.3a | 11.1 ± 33.5a | 11.7 ± 33.4a | 21.4 ± 43.6b | 3.15** |

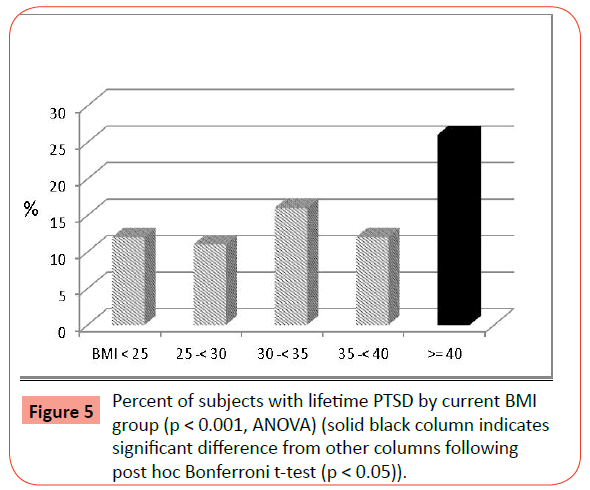

| PTSD (L) | 12.0 ± 31.2a | 11.0 ± 31.9a | 16.0 ± 39.3a | 12.0 ± 34.1a | 26.0 ± 46.8b | 7.60*** |

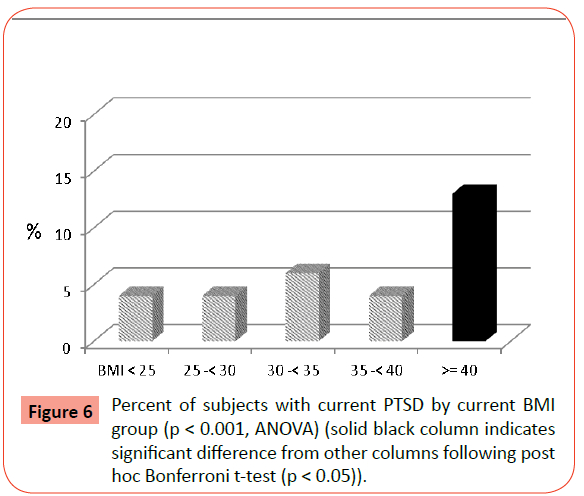

| PTSD (C) | 4.0 ± 10.4a | 4.0 ± 20.0a | 6.0 ± 26.0a | 4.0 ± 20.1a | 13.0 ± 35.6b | 6.76*** |

| Amnesia (L) | 10.1 ± 28.4a | 10.1 ± 31.1a | 16.6 ± 39.8c | 9.3 ± 30.2a | 22.5 ± 44.4b | 8.56*** |

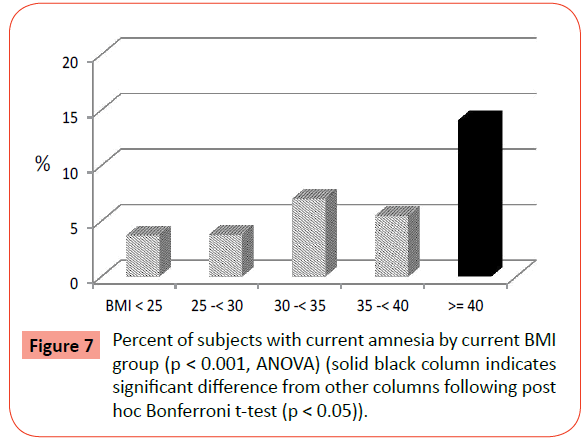

| Amnesia (C) | 3.7 ± 17.8a | 3.8 ± 19.7a | 7.0 ± 27.3a | 5.5 ± 23.6a | 14.1 ± 37.0b | 9.15*** |

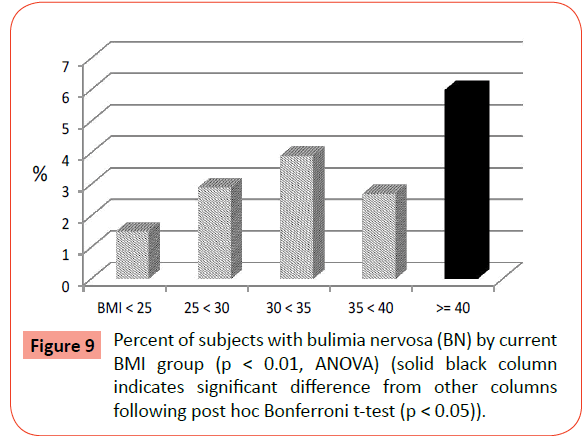

| BN (L) | 1.5 ± 11.6a | 2.9 ± 17.4a | 3.9 ± 20.7a | 2.7 ± 16.9a | 6.0 ± 25.2b | 3.94** |

| BED (L) | 0.8 ± 8.4a | 1.7 ± 13.5a | 2.6 ± 16.8a | 2.8 ± 17.0a | 1.5 ± 12.7a | 2.59* |

| Any ED (L) | 2.3 ± 14.2a | 4.7 ± 21.7a | 6.5 ± 26.3b | 5.5 ± 23.6a | 7.4 ± 27.9b | 5.71*** |

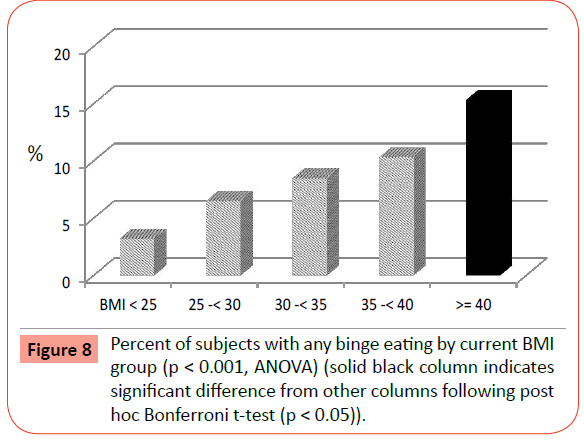

| Any Bingeing (L) | 3.2 ± 16.8a | 6.5 ± 25.5a | 8.5 ± 29.8a | 10.3 ± 31.7a | 15.3 ± 38.3b | 12.65*** |

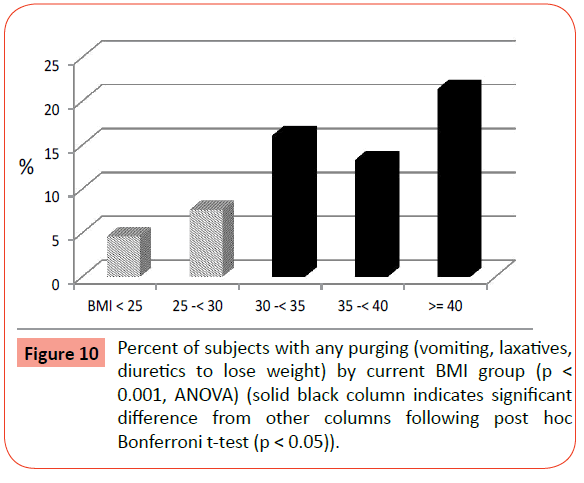

| Any Purging (L) | 4.6 ± 19.9 | 7.6 ± 27.4 | 16.1 ± 29.3b | 13.3 ± 35.4b | 21.4 ± 43.5b | 24.1*** |

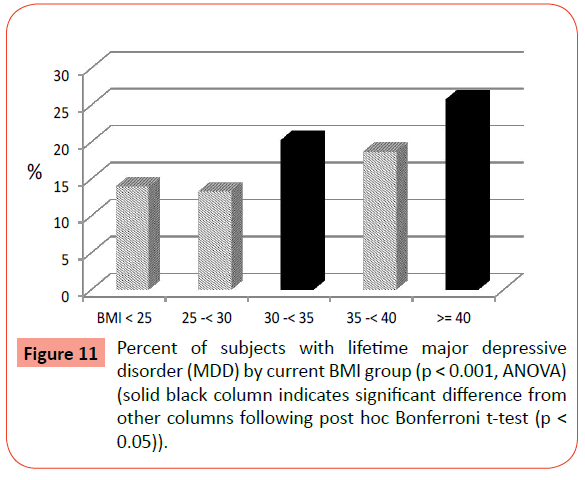

| Major Dep (L) | 14.0 ± 32.9a | 13.3 ± 35.1a | 20.3 ± 43.0b | 18.7 ± 40.6a | 25.8 ± 46.5b | 6.61*** |

| Major Dep (C) | 8.8 ± 26.9a | 8.2 ± 28.4a | 15.2 ± 38.4b | 12.5 ± 34.4a | 18.6 ± 41.3b | 7.70** |

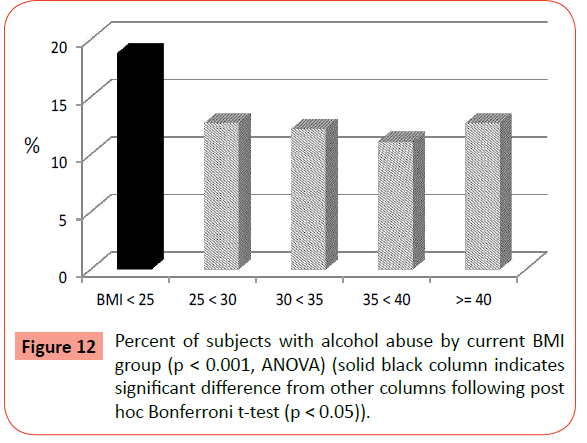

| Alcohol Abuse (L) | 18.8 ± 37.0a | 12.7 ± 34.4b | 12.2 ± 34.9b | 11.1 ± 32.8b | 12.7 ± 35.4b | 5.92*** |

| Alcohol Depend (L) | 7.8± 25.5a | 5.2± 22.8a | 4.6± 22.5a | 2.4±15.8b | 3.8± 20.3a | 4.11** |

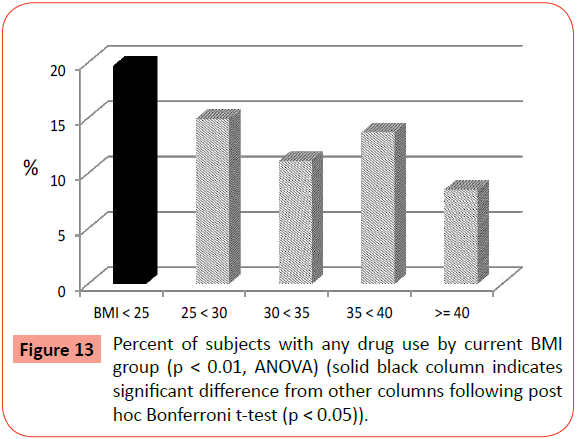

| Drug Use Ever | 19.7±37.7a | 14.9±36.8b | 11.1 ± 33.6b,c | 13.7 ± 35.8b | 8.5±29.7b,c | 7.2** |

Table 2 Variable mean (%) and standard deviation by BMI group with p-value (ANOVA). BN=Bulimia nervosa; BED=Binge eating disorder; CA=Childhood abuse; CSA=Childhood sexual abuse; C=Current; DCV=Direct crime victimization; L=Lifetime; SA = Sexual assault.

***p<0.001; ** p<0.01; * p<0.05.

Significant differences across BMI groups in the prevalence of several crime victimization experiences were reported, including rape at any age, rape during childhood (before age 18 years), childhood sexual abuse (including rape and molestation before age 18), childhood maltreatment (including rape, molestation and aggravated assault before age 18), surviving homicide, as well as any direct crime victimization ever (rape, molestation, aggravated assault, surviving homicide). Of note is the finding that following post-hoc Bonferroni t-tests, the major differences among the BMI groups were between the EO group and all the other BMI groups (Figures 1-4). Molestation, attempted sexual assault, and aggravated physical assault were not significantly different across groups. While the percentage of those surviving homicide was highest in the EO group, this difference failed to reach statistical significance following post-hoc analyses.

There were also statistically significant differences across BMI groups for both lifetime and current rates of PTSD (Table 2). Similarly, women with EO reported significantly higher rates compared to all other BMI groups following post-hoc analyses (Figures 5 and 6). In addition, there were significant differences in the prevalence of current and lifetime amnesia, i.e., forgetting all or parts of traumatic experiences. Post-hoc tests again confirmed significantly highest rates in the EO group for both current amnesia (Figure 7) and lifetime amnesia. In addition, the 30-<35 BMI group also had significantly higher rates than the lower BMI groups and the 35-<40 BMI group for lifetime amnesia.

Significant differences were found across BMI groups for prevalence of ever binge eating, ever purging (vomiting, using laxatives or diuretics) for weight loss, ever having BN, and ever having a bulimic spectrum eating disorder (BN or BED) (Table 2). The rates of BED separately were not significantly different across groups. Post hoc comparisons revealed that only those with EO had a significantly higher prevalence of binge eating (Figure 8) and BN (Figure 9) than the other groups, including the normal weight and less obese groups. Rates of ever purging to lose weight were also significantly higher in all of the obese groups (BMI ≥ 30) compared to the normal and overweight groups (Figure 10). Post-hoc tests revealed that the rates of any ED were significantly higher in the EO group and the BMI 30-<35 group.

There were significant differences among BMI groups for the prevalence of both current and lifetime MDD (Table 2). Both current MDD and lifetime MDD rates (Figure 11) were significantly higher in the EO group and the BMI 30-<35 group compared to all other groups (post-hoc Bonferroni t-test, p<0.05).

Results for lifetime alcohol abuse and dependence as well as ever using drugs (marijuana, cocaine, stimulants, depressants, opiates, psychedelics) were all significantly different across BMI groups (Table 2). However, post-hoc analyses indicated significantly higher rates of alcohol abuse (Figure 12) and drug use (Figure 13) in the normal weight group (BMI<25) in comparison to all the other groups (overweight and obese). Prevalence of alcohol dependence was also highest in the normal weight group in comparison to the others except for the BMI 35-<40 group, which had a significantly lower prevalence.

Discussion

In this study of a large representative sample of US women, we have shown that EO is associated with rape, childhood sexual abuse (including rape and molestation before age 18), childhood maltreatment (including rape, molestation and aggravated assault before age 18), homicide survival, or any direct crime victimization. In addition, women with EO had the highest rates of current and lifetime PTSD, current and lifetime MDD, lifetime BN, lifetime binge eating, lifetime purging, and any bulimic spectrum ED than all other individuals regardless of BMI. These results indicate the importance of subtyping degrees of obesity when studying any possible links with prior victimization, Although lesser degrees of obesity, i.e., BMI 30-<35, were also associated with purging, any ED, current and lifetime MDD, and lifetime amnesia, in most analyses the non-extreme categories of obesity were not associated with prior victimization, PTSD, objective bingeing or BN. These results are in contrast to former studies that did not categorize degrees of obesity according to the NHANES III cutoffs, but instead compared dichotomous groups using a single BMI cutoff.

Crime-related trauma, especially sexual assault and associated PTSD, are important risk factors for development of EO, which is often associated with MDD and BN. These results indicate that only EO and not lesser forms of obesity are associated with a history of trauma and associated psychiatric comorbidity including BN. Although it is clear that any childhood sexual or physical abuse predated the age at maximum BMI, it could be that rape and other forms of trauma occurred after reaching maximum BMI. However, the average age at highest BMI was 32.8 (± 13.1) years as compared to the average age of first interpersonal traumatic experience (14.9 ± 8.2 years) (paired t-test, p<0.0001). Furthermore, the first interpersonal traumatic experience predated the age at maximum BMI in 95% of subjects and in 97.5% of the EO cases.

Careful screening for victimization history and psychiatric disorders in the severely obese is warranted. Generally, this is not standard procedure in most bariatric centers or primary care physicians’ offices. This is an especially critical issue given the significantly higher rates of current and lifetime amnesia for traumatic memories reported in the EO group, as well as the presence of major depression, eating disorders and PTSD, all of which can be associated with great shame. There is both a high potential for under recognition of prior serious trauma and related psychopathology as well as the potential for overzealousness and risk of false memory induction with repeated and/or unskilled questioning. It is unknown to what extent histories of prior victimization and/or the presence of PTSD will influence the course of treatment for EO. However, this would be an important area for future research. Studies of the effects of prior child abuse on the post-operative course following bariatric surgery have been mixed [37-39].

There are several limitations of this study, including its reliance on subjects’ retrospective recall of past experiences. This introduces the possibility of mistakes or distortions in remembering and/or reporting events and experiences. All collected data were based on self-reported responses, which therefore permit individual biases to possibly hinder objective recounting of experiences.

This study is novel in its examination of a number of variables related to victimization, PTSD, eating disorders and related comorbidity in a nationally representative sample of adult women, but the exclusion of men is a significant limitation that restricts the generalizability of our results to women. Future investigations should include men in the sample in order to explore developmental differences across the sexes. However, it is important to note that other studies have reported associations between obesity, earlier life trauma and subsequent PTSD in men [20,22,40].

The strengths of our study include its representative sample of women across the U.S, which makes it generalizable for the population of women at large. In addition, our study asked about various types of crime victimization, such as rape, molestation, attempted sexual assault, and aggravated assault using detailed, unambiguous, behaviorally specific questions. In addition, we used five different categories of BMI according to NHANES III guidelines instead of just two.

Our findings have clear implications for the clinical assessment of women with obesity, especially EO. Our results suggest the value of screenings for past victimization experiences and the importance of early intervention upon onset of binge eating and purging in the effort to prevent the development of full syndrome bulimic spectrum eating disorders, obesity, and related psychiatric comorbidity, such as PTSD and MDD.

These findings also call for a renewed focus on prevention of crime victimization, especially sexual assault, as part of the prevention effort against the development of EO, PTSD, MDD, BN and bulimic symptomatology.

References

- Dansky BS, Brewerton TD, Kilpatrick DG, O'Neil PM (1997) The National Women's Study: relationship of victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder to bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 21: 213-228.

- Dansky BS, Brewerton TD, Kilpatrick DG (2000) Comorbidity of bulimia nervosa and alcohol use disorders: results from the National Women's Study. Int J Eat Disord 27: 180-190.

- Brewerton TD (2007) Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: focus on PTSD. Eat Disord 15: 285-304.

- Brewerton TD, Dansky BS, O'Neil PM, Kilpatrick DG (2015) The number of divergent purging behaviors is associated with histories of trauma, PTSD, and comorbidity in a national sample of women. Eat Disord 23: 422-429.

- Mitchell KS, Mazzeo SE, Schlesinger MR, Brewerton TD, Smith BN (2012) Comorbidity of partial and subthresholdptsd among men and women with eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey-replication study. IntJ Eat Disord 45: 307-315.

- Brewerton TD, Brady K (2014).The role of stress, trauma, and PTSD in the etiology and treatment of eating disorders, addictions, and substance use disorders. In: Brewerton TD, Dennis AB (eds.). Eating Disorders, Addictions, and Substance Use Disorders: Research, Clinical and Treatment Perspectives. Berlin: Springer, 379-404.

- Wonderlich SA, Brewerton TD, Jocic Z, Dansky BS, Abbott DW (1997) Relationship of childhood sexual abuse and eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36: 1107-1115.

- Jacobi C, Fittig E, Bryson SW, Wilfley D, Kraemer HC, et al. (2011) Who is really at risk? Identifying risk factors for subthreshold and full syndrome eating disorders in a high-risk sample. Psychol Med 41: 1939-1949.

- Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras WS (2004) Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol Bull 130: 19-65.

- Felitti VJ (1991) Long-term medical consequences of incest, rape, and molestation. South Med J 84: 328-331.

- Felitti VJ (1993) Childhood sexual abuse, depression, and family dysfunction in adult obese patients: a case control study. South Med J 86: 732-736.

- Kanter RA, Williams BE, Cummings C (1992) Personal and parental alcohol abuse, and victimization in obese binge eaters and nonbingeing obese. Addict Behav 17: 439-445.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, et al. (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 14: 245-258.

- Alvarez J, Pavao J, Baumrind N, Kimerling R (2007) The relationship between child abuse and adult obesity among california women. Am J Prev Med 33: 28-33.

- Bentley T, Widom CS (2009) A 30-year follow-up of the effects of child abuse and neglect on obesity in adulthood. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17: 1900-1905.

- D'Argenio A, Mazzi C, Pecchioli L, Di Lorenzo G, Siracusano A, etal. (2009)Early trauma and adult obesity: is psychological dysfunction the mediating mechanism? PhysiolBehav98:543-546.

- Noll JG, Zeller MH, Trickett PK, Putnam FW (2007) Obesity risk for female victims of childhood sexual abuse: a prospective study. Pediatrics 120: e61-67.

- Rohde P, Ichikawa L, Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Linde JA, et al. (2008) Associations of child sexual and physical abuse with obesity and depression in middle-aged women. Child Abuse Negl 32: 878-887.

- Sansone RA, Schumacher D, Wiederman MW, Routsong-Weichers L (2008) The prevalence of childhood trauma and parental caretaking quality among gastric surgery candidates. Eat Disord 16: 117-127.

- Gunstad J, Paul RH, Spitznagel MB, Cohen RA, Williams LM, et al. (2006) Exposure to early life trauma is associated with adult obesity. Psychiatry Res 142: 31-37.

- Aaron DJ, Hughes TL (2007) Association of childhood sexual abuse with obesity in a community sample of lesbians. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15: 1023-1028.

- Vieweg WV, Julius DA, Bates J, Quinn JF 3rd, Fernandez A, et al. (2007) Posttraumatic stress disorder as a risk factor for obesity among male military veterans. ActaPsychiatrScand 116: 483-487.

- Perkonigg A, Owashi T, Stein MB, Kirschbaum C, Wittchen HU (2009) Posttraumatic stress disorder and obesity: evidence for a risk association. Am J Prev Med 36: 1-8.

- Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Bodenlos JS, Appelhans BM, Whited MC, et al. (2012) Association of post-traumatic stress disorder and obesity in a nationally representative sample. Obesity (Silver Spring) 20: 200-205.

- Kubzansky LD, Bordelois P, Jun HJ, Roberts AL, Cerda M, et al. (2014) The weight of traumatic stress: a prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and weight status in women. JAMA Psychiatry 71: 44-51.

- SAMHSA (2014) SAMHSA's Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. In: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration OoP, Planning and Innovation (ed.) Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, pp. 1-27.

- Brewerton TD (2011) Posttraumatic stress disorder and disordered eating: food addiction as self-medication.JWomens Health (Larchmt) 20: 1133-1134.

- Brewerton TD, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG, O'Neil PM (1999) Bulimia nervosa, PTSD, and forgetting results from the National Women's Study. In: Williams LM, Banyard VL (eds.)Trauma and Memory. Durham: Sage, pp. 127-138.

- Simon GE, Von Korff M, Saunders K, Miglioretti DL, Crane PK, et al. (2006) Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63: 824-830.

- McCarty CA, Kosterman R, Mason WA, McCauley E, Hawkins JD, et al. (2009) Longitudinal associations among depression, obesity and alcohol use disorders in young adulthood. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 31: 442-450.

- Back SE, Waldrop AE, Brady KT, Hien D (2006) Evidenced-based time-limited treatment of co-occurring substance-use disorders and civilian-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Brief Treatment Crisis Interven6:283-294.

- Brady KT, Killeen TK, Brewerton T, Lucerini S (2000) Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 61: 22-32.

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press.

- Brewerton TD, Rance SJ, Dansky BS, O'Neil PM, Kilpatrick DG (2014) A comparison of women with child-adolescent versus adult onset binge eating: results from the National Women's Study. Int J Eat Disord 47:836-843.

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL (1993) Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. J Consult ClinPsychol 61: 984-991.

- Kuczmarski RJ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM, Troiano RP (1997) Varying body mass index cutoff points to describe overweight prevalence among US adults: NHANES III (1988 to 1994)Obes Res 5: 542-548.

- Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH (2006) Relation of childhood sexual abuse and other forms of maltreatment to 12-month postoperative outcomes in extremely obese gastric bypass patients. ObesSurg16:454-460.

- Clark MM, Hanna BK, Mai JL, Graszer KM, Krochta JG, et al. (2007) Sexual abuse survivors and psychiatric hospitalization after bariatric surgery. ObesSurg 17: 465-469.

- Mitchell JE, Crosby R, de Zwaan M, Engel S, Roerig J, et al. (2013) Possible risk factors for increased suicide following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21: 665-672.

- Fuemmeler BF, Dedert E, McClernon FJ, Beckham JC (2009) Adverse childhood events are associated with obesity and disordered eating: results from a U.S. population-based survey of young adults. J Trauma Stress 22: 329-333.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences